Born in Trinidad in 1915, Claudia Jones grew up in Harlem in the early part of the 20th century. Her family moved there when she was a child, as the post-war recession took hold of the Caribbean island, although their fortunes didn’t fare much better in the US. Her family struggled to make ends meet, and things only got worse when Jones’ mother passed away when she was just 12 years old. Jones was academically bright, but suffered from tuberculosis from a young age, which affected her studies. She was unable to attend her own graduation ceremony as her dad couldn’t afford to buy her a gown.

After school Jones took a series of menial jobs, including working in a laundrette, until the case of the Scottsboro Boys inspired her to join the American Communist party. The Scottsboro Boys were nine black youths wrongfully accused and convicted of raping two white girls on a train – the Communist Party had helped to get them a proper defence for their re-trial (despite this all served lengthy jail terms, with just one of them being pardoned while still alive). Here was a political party that dared to defy the racism ingrained in the establishment, and Jones wanted to be a part of it.

Identifying herself as a Marxist-Leninist, Jones’ eloquence led to her becoming one of their spokespeople as well as the editor of the party’s newspaper. By the age of 25 she was the National Director of the Young Communist League; she also travelled the country giving public speeches, and wrote for the Daily Worker and the Weekly Review, both left wing publications. But this was the 1940s, when McCarthy’s witch hunt was in full swing and communists were viewed as enemies of the state. Jones was sent to prison on more than one occasion, the first time being in 1948, but she refused to stop campaigning. Eventually she was deported, and in 1955 she came to the UK.

\n\nOnce in London, the British Communist Party showed little interest in the contributions of a black female. In 1958 Jones decided to found her own newspaper, one that spoke about the rights of Afro-Caribbean people, the West Indian Gazette. This paper not only dealt with civil rights, employment rights and social injustice, it also focused on the arts and world politics.

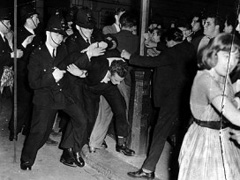

This was also the year of the Notting Hill Riots. In the 1950s the first wave of immigrants arrived from the Caribbean, as the British economy was starting to flourish again after years of post-war depression. The British government welcomed the new arrivals, who came to work, filling gaps in the workforce. Many settled in Notting Hill, but unfortunately this was also the home of the National Labour Party, a far right political party set up to oppose non-white immigration.

Although not quite as hostile as America, London in the 1950s was not kind to black people; a wall by St. Matthew’s Church in Brixton boldly proclaimed “Keep Britain White”, and white and black people were largely segregated on public transport and in pubs and bars. The Race Relations Act, which put in place laws against discrimination based on race, didn’t come into effect until 1976.

The West London neighbourhood became a hot bed of racial tension and violent attacks, culminating in the riots and the killing of Kelso Cochrane, a young carpenter from Antigua. He was assaulted by a group of white youths who were never caught, and although the police quickly classed the case as robbery, it was widely believed the crime was racially motivated.

\n\nThe year after the riots, Jones decided to set up an event to promote West Indian culture and build bridges between communities, an attempt to put the troubles in the past. The idea of a mardi gras was suggested, although it was winter and so would have to be held indoors. The first event was an evening of Caribbean music and dancing which took place at St. Pancras Town Hall, and Jones arranged for it to be broadcast on the BBC. It was to be repeated for the next five years, until the first Notting Hill Carnival was organised in 1964. Today the carnival draws a crowd of around a million people on each day of its two days, second in size only to the famous carnival in Rio de Janeiro.

Claudia Jones passed away that year at the age of 49, but she did get to witness the carnival. After a lifelong battle with health problems stemming from the tuberculosis she was afflicted with as a child, she died of a massive heart attack. She is buried in Highgate Cemetery, next to her ideological hero, Karl Marx.

In 1982, almost 20 years after her death, the Claudia Jones Organisation was established. The charity provides an advocacy service for Afro-Caribbean women and families, with services ranging from music lessons to parenting courses.

One of the most enthralling street parties in the world would never have happened without Claudia Jones, but this is the least interesting thing about her legacy.

See also The History of Notting Hill.