The tradition of sewing pearl buttons onto clothing comes from the costermongers, traders who scraped a living by selling fruit and veg from hand baskets or donkey carts as far back as the 11th century (in case you’re wondering, their name comes from “costard”, a type of apple that no longer exists).

Being a costermonger wasn’t easy, as their livelihood depended on the seasons and the day to day weather. The first few months of the year were the toughest as there was little produce to sell; rainy days were bad too as customers stayed indoors. They bought wholesale and sold for a small profit, plus they were forever in debt as they had to buy on credit.

Costers travelled around working at different markets without licences, they were often hassled by police if they suspected them of loitering. They also earned themselves a reputation for drinking heavily, however given the times (consider what little respite a Victorian coster would have had) this is hardly surprising. In time the word “costermonger” became a bit of an insult.

This apparent disapproval would have had much to do with class, as the costers were not a bad bunch; they were tight-knit, generous and helped each other out when times were hard. They even developed their own vernacular before the days of Cockney rhyming slang, something which came in handy when the authorities were around.

When London expanded beyond the limits of the City walls the costermongers decided to get organised by electing a leader for each borough, called a ‘king’ or ‘queen’. The person chosen would face an uphill struggle lobbying for their rights; the shy and the submissive didn’t need to apply.

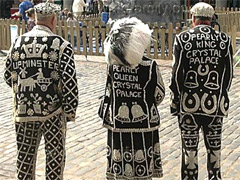

\n\nBy mid-19th century the costers had their own uniform: light coloured cord waistcoats adorned

with brass buttons along the seams, or dark waistcoats with mother of pearl buttons,

which helped to disguise worn clothes. The men also wore bell-bottomed corduroy trousers and

silk neckerchiefs.

But the costermongers weren’t yet Pearly Kings and Queens. A boy called Henry Croft grew up in an

orphanage in Somers Town, till 1875 when at the grand old age of 13 he decided to leave and fend

for himself. He started working in the local market as a rat catcher and road sweeper, and he was

soon on friendly terms with the costers.

Inspired by the community spirit of his new friends, the young Henry took it upon himself to raise

money for the orphanage he’d recently left, but knew he would need a novel way to attract people’s

attention. Inspired by the costermongers’ outfits, he collected all the pearl buttons he could find and

completely covered his clothes in them, even his cap, once he’d been taught how to sew.

His idea worked, and when word spread of his charitable work for the orphanage, hospitals,

workhouses and churches asked him for help. There was no way Croft could cope with this demand,

so the wily lad recruited the costermongers to help out. Naturally they followed him in the style

stakes, with ever more flamboyant costumes – the Queens even wore ostrich feathers.

This team of fundraisers grew to the extent that separate groups were formed, such as the Pearly

Guild in 1902, and the Pearly Kings and Queens Association in 1911. Unsurprisingly this led to

rivalries, however the aim remained the same: to raise money for the less fortunate. The

London Pearly Kings and Queens Society is derived from Croft’s collective.

\n\nBy the time Croft died in 1930, aged 68, there was a King and Queen for each borough. Croft’s

funeral was a grand affair complete with horse drawn carriages, as befitting someone who’d raised

thousands for charity. The event was filmed by British Pathe, and the final footage bears the intro

“Pearly Kings & Queens from every part of London pay last tribute to their revered Chief, Mr Henry

Croft”. Several of the organisations he’d helped in his lifetime paid for a statue on his gravestone,

however this was vandalised in 1995 and has since been moved to St. Martins in the Field.

Different groups still thrive, and there are Kings and Queens for boroughs as well as

neighbourhoods such as Mile End and North Kensington. Their offspring are called Princes and

Princesses, until in theory they’re old enough to inherit their parents’ titles - Croft’s great

granddaughter is the Pearly Queen of Somers Town. They continue to raise funds for many different

charities, from Cancer Research and Marie Curie to the Donkey Sanctuary and the Surrey Air

Ambulance. Money is usually collected during big public events, or at Pearly King and Queen

coronations.

The Harvest Festival is the biggest date in the Pearly calendar. Every September or October the

Pearlies march through the City of London, with a band and folk dancing adding to the occasion. The

parade ends at St. Mary-Le-Bow church in Cheapside, where a thanksgiving service for autumn’s

harvest takes place. As well as being a fundraiser, the event honours almost 140 years of tradition

and more than a little East London pride.